More Matata – Book 2

Love After the Mau Mau

We return to our protagonist Lando, as the rumble of civil strife breaks out. The country is segregated and seething with tensions after the Second World War. The ‘terrorists’ are chased by colonial troops away from the white highlands into the forests, and then into the urban areas of Nairobi, Nakuru, among others. They infiltrate into servants’ quarters of the Asian community. It is an unsustainable struggle as Britain announces the ‘Winds of Change’ and colonial barriers are eased. Lando reaches adulthood and the country attains its independence. Matata means trouble in Swahili. Falling in love across racial barriers is big matata, especially in Kenya.

The country is segregated and seething with tensions after the Second World War. We return to our protagonist Lando. His return to Kenya is timed with the increased presence of the Mau Mau, a secret organization determined to overthrow the colonial government. The Mau Mau is slowly spreading its grip of terror from the far-off White-settler occupied Highlands into the urban areas, around Lando’s school and allegedly into his home. The winds of change are already gusting across Africa and the rest of the world.

In a few years, the Portuguese and British are forced to give up their colonies in India and East Africa respectively. Just as the racial barriers fall, the Goans who have lived under colonial rulers for over 450 years, are left rudderless and stateless. In spite of all this matata, Lando and the beautiful Saboti meet again under extraordinary circumstances, and that is the biggest matata of them all.

Reviews

For those of you who have ties to Goa, Kenya, Mozambique, Seychelles, life in the 1950’s, Mau Mau, 1960’s …. you will find this book MORE MATATA by Braz Menezes just awe striking! I have just finished the book.

I, at the age of 71 realize now why I am what I am. It’s very important to know history to know the truth of things. The crevices of my brain were touched big time. Racism, where the British were next to God Almighty. The Asians were divided into caste and religion. Then people like me were half breeds, half caste, “chotara”. The native Africans were marginalized! There were segregated schools, clubs and even the Catholic Church had pews reserved for the whites! We, the mixed race belonged nowhere and everywhere. So very disgusting it was, as Apartheid existed big time in those days.

In the book there are also some intriguing parts of tear-jerking love between the Goan boy Lando and Saboti, the ritual of the dancing Zebras, the pink Flamingoes fluttering in the Lake Nakuru, Magadi and Masai Mara.

I was the happiest person on Earth when I moved to London in 1971 as that kind of segregation did not exist to that degree. I even remember feeling: I am just worthy as a white person😯 I was accepted and am so happy to be that mixture of all colours!

However, I know now why I am as sensitive as I am. I know why I may feel “do they really like me?” I always find out that I am loved most of the times and not the contrary. But this is coming from then “colour bar” and segregated Africa in my times growing up there. I did not really realize this until now.

Thank you, Braz.

For the first seventeen years of my life, I lived in Nairobi, Kenya. I left in 1951 and except for a brief holiday in 1988, I’ve not visited the country until Just Matata and More Matata whisked me back in time. However, the mind never forgets what the heart has experienced, the bitter as well as the sweet. Memories are made of this.

Lando’s narratives took my heart back to some of the most memorable and happiest moments of my life. I was transported back sixty-five years on the magic carpet of his eloquence to 1939 when I remembered the many times I travelled between Nairobi and Mombasa. Mention of the various train stations in between the two cities brought back memories of the “exotic” names: Mariakani; Maji ya Chumbi; Manyani; Voi; Makindu; Tsavo. In his descriptions, I could see the Athi Plains teeming with wild animals.

His stories also stirred up some of the most painful and not so happy memories of the colour bar (racial segregation) like the separate entrances, second-class compartments, restrictions on access to public spaces, and all the other shameful discriminatory practices in British East Africa at the time. And, not least, the racial slurs and taunts even within our own communities when one married outside of their heritage.

As a son of a Goan father and a mother from the Seychelles, as a child, I experienced life often as an outsider, never quite fitting into either community. Lando’s awareness of these divides was the first time that I realized someone else understood, and was deeply aware of the pain that it caused. In a very personal way, I was moved by his considerable insight of racial issues, and the enormour sensitivity of his nature. Lando demonstrated an uncommon perception of racial tensions, when at an early age he expressed his affection for a young girl whom he knew was different from his culture. He revealed his deep love for a woman who he knew would certainly garner disapproval of some in the community, and showed his determination to overcome the difficulties that he faced throughout his life.

Lando was a man of principal and character. When Lando spoke about his experiences at St. Francis Xavier Church, I was transported back to the same church where I served mass with Father Butler, confessed my “dreadful” sins, and almost on the same day, stole guavas from the trees around the church grounds.

Different races were also segregated in church. His mention of the Goan School, the Coryndon Museum, and the Goan Gymkhana brought a smile to my lips and a twinkle to my eyes, as I reminisced about my innocent misbehaviour, my love of sports and the many friendships forged.

It stuck with me that there were very few elements of fiction in the books. It is far more than a life story and life history. It intelligently portrays the significant contributions that Goans made in the early development of a country, and subtexts of the racial inclusions and exclusions existed at the time.

Braz Menezes’ Matata books are thoughtful, extremely evocative, and very easy to read. Please don’t stop writing, Braz!

I finished reading More Matata, a novel by Braz Menezes, a few days ago. It is a very good novel. The protagonist is called Lando and in this, the second novel in a trilogy, he focuses on a lot of the give and take of political issues in Kenya from the ’50s up to the early ’60s. Lando provides realistic and passionate discussions between Goans who have different points of view about the issues that concern them and their future such as the take over of Goa by India in 1961; the forthcoming Independence of Kenya in December 1963; the portraits and actions of the most powerful African politicians in Kenya; etc.

I had made a few comments and asked a few questions in Goa Book Club after reading Volume I. Specifically, I wondered how it was possible to tell the story of Goans working for the civil service in Kenya during a time of Mau Mau without mentioning the Mau Mau at all. But I see now that my questions were being answered in Volume II, subtitled “Love After the Mau Mau”. Lando not only knew everything I asked, he knew it in fuller detail than I did. What I thought were secrets mentioned in whispers were actually given expression directly by different people in Kenya. They were only whispered in the Ministry of Finance in Uganda, where I worked in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

The second novel is very political. Lando describes the landscape, the flora and fauna, with great depth and insight. But it also includes the people, something barely noticed by tourists busy watching animals making love instead of people fighting to get back their land. Lando went everywhere in the country, not only out of curiosity but also following his occupation after graduation as an architect. His father was a bank employee and member of the Goan Gymkhana, full of civil servants, so he grew up being aware of what was going on. Being an architect gives him a particularly practical way of looking at and seeing everything.

I have a question when it came to Saboti, mentioned in the first volume and in more depth in the second. When she returns into Lando’s life and he finds out more about her, he realizes she is not from Seychelles as he had thought: she was English through her father and Masai through her mother, so she was nusu-nusu, half and half. My question: Lando loses her in England after too short a time apart, loses her to an Englishman. At this time, love across the races was difficult — but what happened would suggest that their love was not love but infatuation. Yes, such a relationship across colour lines would be difficult at that time, but the novel gives examples of overcoming such a barrier such as Joseph Murumbi, whose father was Goan and mother Masai. But the ultimate meaning of the relationship will depend on what is presented in Part III.

Lando is a good storyteller. He is observant and has a wide and deep knowledge and is sympathetic to the Kikuyu people over their land alienation and yet is not blinded to political betrayals or to the scheming of the British. By good storyteller, I mean that several episodes are very dramatic. The chapters are short, almost anecdotal. There is a fine sense of humor and irony in the chapter titles.

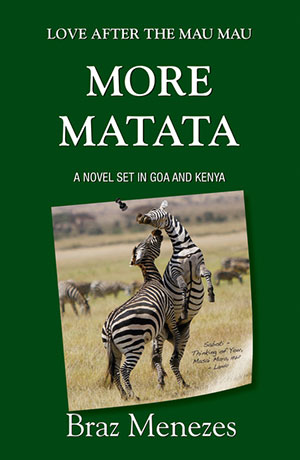

Menezes’ way of structuring the novel is not external like an architect but internal in that certain images become iconic and represent more than what they seem to be such as the cover image of the two zebras attempting to kiss. What does this mean? We have to figure it out. Maybe it has more than one meaning.

In his acknowledgements, Menezes says that most people are unaware of the special culture of Goans that developed under 450 years of Portuguese rule. The point is WE EXIST! We do not define ourselves through tourist brochures, we are not like zebras for tourists to gawk at, though the black and white colours of the zebras could be a metaphor for Goans, who have combined cultures, East and West, who have not merely resided where they went, whose children became part of the people and the land and had an awareness and made contributions. A big struggle for Goans has been to prove that we exist as a people.

But after the event, after decolonization, the task is even more important: Goans are being made invisible and that what they achieved seems to be in danger of being lost to history. What is history? On one level, it is a record of what happened. If there is no record, what happened disappears, and so do the people.

Lest one gets too caught up in the stereotype of the obedient Goan civil servant, one should pay attention to the text. The Goans were not totally obedient and did not stay out of politics. On the contrary, More Matata provided details and portraits of Goans who were anti-colonial political activists such as Pio Gama Pinto, JM Nazareth, and others. Pinto was imprisoned by the British and after independence, he was elected to parliament in an African constituency. He was assassinated in early 1965 and is considered to be Independent Kenya’s first martyr without any concern about the fact that he was a Goan. To this day, questions are asked about who killed him — when it is well known who did and why. So the notion that Goans stayed out of politics was a cover for political involvement in Kenya and an ongoing debate about whether those working for the British could go against British interests. A lot of such debates take place in the novel in the Goan Gymkhana and the other Goan institutes.

If you want to read Diaspora history and relate to it, there is nothing better than to get it from the perspective of someone who lived through it, has a talent for vivid memories and sequences, can recount it well enough to hold your interest and more importantly has no agenda in the telling.

By those standards, Braz Menezes’ More Matata now available in selected bookstores and on Amazon is a book worth reading not just by the Goan community, but by everyone else who enjoys being transported to an era that seemed more simple but was not. Braz has accomplished a fluid continuation from his first book, Just Matata, so that even the reader of solely this second book of the trilogy, finds nothing missing.

While the previous story is of Lando’s early childhood and is virtually bereft of any of the politics that prevailed in East Africa in the mid-20th century, the author does not shy away from those prickly issues in this one. A good part of the current narration revolves around the Mau Mau rebellion of the Kikuyu tribe of Kenya as seen from the daily life of a young man in Nairobi. The politics of the time do not totally cloud the author’s writing. There is still enough devoted to the real story — that of a young boy becoming a man living in a society that we would find hard to understand in today’s world and yet can sympathetically view it from Lando’s growing up.

The unhitching of a country from its colonial presence always makes interesting reading when done many years after. When lived by the settler-people of that day, it is always traumatic. To narrate this without seeking sympathy or victimhood is creditable. When told matter-of-factly, it makes for a good book.

Picture communities living the good life in a beautiful country not their own, though not without the many sacrifices they have to endure. Imagine the turmoil they find themselves in when the yoke of colonialism is finally being unburdened. And then when the process of freedom is almost complete, feel what they feel when told that they have no place in the new country despite living for generations in it. All of that happened in Kenya and Braz Menezes records it for posterity. Not much has been written about this except for the coldly historical, so such writings must form a reference for those who one day need to come back to that age and experience.

More than a little space has been devoted to Lando’s love affair with his childhood sweetheart Saboti. I would have preferred a little less of that and more of something else. However, an author writes what he feels and not according to a critic’s dictates. Menezes can therefore be forgiven for that.

Not much has been written about the Goan experience in East Africa besides the books of Mervyn Maciel, Theresa Albuquerque and now Menezes. Therefore, a novel such as this becomes valuable and not to be missed. Goans can be great debaters like the Bengalis. But when it comes to recording what they experienced, they seem to be singularly lacking.

To a non-East African Goan like myself, every written word becomes a treasure chest to be opened. These thoughts are not a critical view of what Menezes has written (I leave that to others), but rather an acclaim of his having written it in a way that is pleasurable and informative. I hope others from East Africa, especially Uganda about which there is virtually nothing, follow Menezes’ path.

Gerhard A. Fuerst is retired adjunct professor of social science at Western Michigan University.)

What in my estimation makes the historical novels of author Braz Menezes so fascinating is his lively and exciting narrative style, which entices the reader to follow him wherever he guides, lures, and leads you, often with a very delightful sense of self-deprecating humor. Books one and two, published to date, of his Matata Trilogy, with number three being a work in progress, are essentially biographical in nature. It is history lived and experienced in actuality!

Both in content and context, the unfolding historical scenarios are most convincingly and reliably related by the characters in his novels, with whom Lando, central to all aspects of personal and public events, both in a routine, extraordinary or exceptional sense, shared his many adventures and exploits. He got into all sorts of matata at times, which again mandated clever attempts or tricks of extrications. Youth after all is the time of stretching and testing given parental and social norms, learning both by one’s wit and by one’s mistakes.

It is also the story of his scores of school mates and his very persuasive and influential teachers, his neighbors and family friends, and all others he and his family encountered and interacted with on a daily basis or in their narrowly defined and designated social settings, shaped first and foremost by family, school, church, and the community’s social club.

In a very skillfully and lovingly crafted literary style, Menezes makes the reader fully aware what it was like to grow up in the British Colony of Kenya. He clearly delineates what challenges and risks people were confronted by, what limitations or restrictions in personal mobility, educational and occupational opportunities, and racial residential compartmentalization. It was both external and internal colonialism, perhaps even a form of imposed ghettoization. People faced innumerable dilemmas as they tried to wind their ways through the meandering and often conflicting trials and tribulations of a multi-racial, multi-cultural, multi-lingual, multi-religious social construct.

The many Goans migrating from Portuguese India to East Africa, coming with skills and a willingness to work with distinction and dedication, were able to fit in and make do entirely without, or with whatever was permissible or available. You had to find your niche where you could exist with a sense of normalcy, both in private and in public. You had to learn to survive. You had to bear the economic burdens, and to make the best out of very limited social opportunities, in order to rise to the top at a level allocated to you and your kind. You learned to be the best you could be in this social conglomeration, a multi-layered cultural complex with many communities being compelled to coexist under strictly enforced segregated conditions, with very significant differences and inevitabe tensions, not only between but also within. You were manipulated at will by the colonial power and you had to prove yourself to be a genius at survival. Goans managed to do that, and in doing so, helped in building the administrative capacity, infrastructure and the economy of the colony, as was demanded of them at the time, and later of the independent country.

Lando resumed his education in Nairobi, adjusting to what had transpired in his absence. Changes of schooling had become necessary, as new opportunities presented themselves. This involved switching from a Goan Catholic setting to a non-Catholic public school with a new focus on imparting technical skills for work opportunities to be created or demanded by the thoroughly class- and race-conscious British colonial government.

As mentioned before, the narrative is so compelling, you cannot help but identify with Lando and his varied matata plight, both real or imagined. In fact, the reader is virtually transformed in becoming Lando, and living his life with him and for him. He needs both reassurance and understanding, as he faces teenage temptations, and as he overcomes difficulties in a post-World War II society. These have both direct and indirect domestic consequences, affecting social relationships and old friendships as one erstwhile colony after another sought to extricate itself from under the externally imposed colonial yoke.

These struggles were incredibly violent, brutal and bloody, and it left an internally divisive colonial legacy, which lingers and languishes to this day. Kenya experienced the pro-nationalist Mau Mau Emergency and gained its Independence from British rule in 1963. This necessitated also a very painful reshuffling of the social settings, forcing Goans and other immigrant races to either remain by trying to stake a claim in the possibilities and the process of independent nation building, or to leave. Returning to their ancestral homeland of Goa was for many still an option, however in 1961, this former Portuguese colonial enclave had been seized by India in a very move of swift imperialistic military might, which the victors later on in somewhat over-bearing and arrogant ways referred to as their “war before breakfast!”

Lando and his family made the most of what had been given to them, and what they had created for themselves based on their own tireless, dedicated, frugal efforts and hard labors. He also rediscovered a love he had long nurtured for Saboti. Friendship in due time becomes romance and real love. For that reason alone, Lando was intent to reach across very complex racial barriers, and socially imposed taboos, dictated by notions of caste and class.

Alas, Saboti, moved to London to seek other employment opportunities, in part also to escape a dangerously deteriorating situation in Kenya, with the Mau Mau insurrection causing chaos. Lando’s dreams of personal happiness were dashed. He ultimately found fulfillment in architecture and urban planning. He and Saboti encountered each other again later on in life, by sheer chance, after many decades had passed. Their friendship was renewed. She and Lando were again reaching out to each other, both at the beginning of book two and at its end….it is like a very loving and kind-hearted literary embrace by long lost friends in need of personal comfort and mutual reassurance.

Braz Menezes’ second volume continues the story of Lando and the Goan community in East Africa after the young man returns from his unhappy time in a boarding school back in Goa. It follows him through the upheavals of the Mau Mau rebellion and towards independence for Kenya in 1963. The book actually connects the reader to even more modern events on the eve of the election of Barack Obama (with his own Kenyan connections) to the presidency of the United States and to the backdrop of Kenyan political upheavals following their own 2007 elections. The author cleverly links these two events to the final days of empire in East Africa and gives some insight into how the seeds for future disruption and discord were sown in the last days of British rule.

The story reveals that there is both an element of individual choice in attitudes to race whilst still having to work within constraints or expectations from a surrounding culture or group of people. So, soldiers, settlers, British, Goans, Africans, tribes, rich, poor… might all have an umbrella starting point to racial attitudes, but each individual can select for themselves whether to embrace those group norms or forge ideas and concepts of their own…None of this is stated outright in the book, but careful reading allows you to follow a multiplicity of attitudes towards race in a part of the Empire that had very much been defined by racial differences and found itself catapulted towards having to address these issues sooner than it had anticipated.

The first over manifestation at having to confront issues of race, tribal identity and raw power politics was in the form of the Mau Mau rebellion in the 1950s. …Once again, the book does a good job at explaining how the realities of this emergency seeped into the everyday lives of all concerned – even the liberal British teachers who found themselves uncomfortably carrying around pistols to defend themselves from unknown Africans – the very people some of them presumably were keen to come to Kenya to help in the first place.

The conflicting views of Goans themselves towards independence and the Mau Mau form a powerful thread through this second book. There are those who sympathise with the aspirations of Africans but appreciate that their own community had been some of the biggest beneficiaries of European rule with their relatively privileged positions in government and leading industries and businesses at least vis a vis the Africans. Idealism conflicts with realism for all too many and the steady stream of Goans heading for the exit through the 1950s and early 1960s help illustrate that the

The book also introduces Lando to the difficulties and realities of love with the enigmatic Saboti being the object of his affections. The love story is also an opportunity to examine the difficulties and issues of mixed race births and inter-racial relationships in what can make for uncomfortable but important reading. Of course, even the Goan community’s own, often close-minded, attitudes towards mixed relationships enters the fray and the way that even though they are predominantly Catholic in culture, many of their attitudes towards race and caste at times appear not to veer that far from Hindu Indian attitudes or at least might be characterised as deeply conservative in origin. Again, it would be all to easy for an author to brush over difficult and embarrassing issues and tell a hagiographic story of progress and virtue. Hats off to Braz Menezes for not shying away from difficult issues and addressing them in a highly believable and informative manner.

Once again, the author manages to continue to weave the compelling story of the Goan community through the very last years of imperial British rule and takes Lando’s story through to the new dawn of an independent Kenya.

Mervyn Maciel is the author of Bwana Karani.

Following so soon after his original book Just Matata, Braz Menezes is to be commended for not keeping us waiting for the second in this trilogy. More Matata, now available through Amazon and other outlets is equally interesting and entertaining.

While politics was not the dominant feature of Just Matata, in his latest book, Menezes recounts the events, some quite bloody, which saw Kenyans finally shake off the yoke of Colonialism and usher in a new era in an independent Kenya. The Mau Mau rebellion (originally confined to the Kikuyu tribe), the State of Emergency, the Kenyatta trial and its aftermath, are all given extensive coverage in the various chapters. This should provide a valuable insight about the situation in Kenya and how the Goans and other communities coped, especially to those who have never lived in Kenya.

For me, a former civil servant of colonial and independent Kenya, some of the chapters revived memories of old friends like Pio and Rosario Gama Pinto, Olaf Ribeiro, L. D’Cruz and many others who feature prominently in the pages of this book.

Lando and his friends relied heavily on the BBC World Service for news, but there was also the other “Goan Grapevine Service” often provided by visiting Goan civil servants from up-country who, throwing caution to wind and forgetting they were all bound by the Official Secrets Act, freely dispensed with the latest news on the security situation during the Emergency. This no doubt from the “inside information” they had as trusted civil servants.

If like me, you have enjoyed Just Matata, you will find it hard to put down More Matata.

Mel D’Souza, born in Tanzania, went to school in the Goan village of Saligão and is the author of Feasts, Feni and Firecrackers: Life of a Village Schoolboy in Portuguese Goa (2007). He lives in Brampton, Ontario with his wife, Lineth.

At last we have a book that answers the who, what and why for the distinct Goan society. More Matata by Braz Menezes is a book that needs to be read by anyone who may wish to learn more about Goans, and particularly by those with Goan roots who seem to be striving in vain to “discover their identity.”

In More Matata, Braz Menezes has painted a photographic picture of the quintessential Goan without the embellishments that preoccupy many other Goan writers.

Goans can be found in every society anywhere in the world, while being notably inconspicuous. This trait is a legacy of their Portuguese heritage that goes back to 1510 when the Portuguese invaded Goa and declared it as Portuguese territory. In the process of converting the populace to Christianity, they insisted on total assimilation with their European masters.

In the ensuing centuries, assimilation became a Goan trait and enabled them to blend into the mainstream in any society they chose to live in. And this they did very successfully when they ventured beyond the boundaries of Goa to find ready employment in countries that came under the realm of the then mighty British Empire, and the once adventurous Portuguese Throne.

In More Matata, Menezes has defined the classic Goan in a way that makes for easy reading. It’s devoid of academic research, deep analysis, or boring introspection. Instead, the free-flowing story gives the reader an insight into the Goan psyche and a way of life during Britain’s colonial era as seen through the eyes of Lando, a young Goan boy and, later, as a young adult.

More Matata is the second book in the Matata trilogy about the life of Lando. The first book, Just Matata: Sin, Saints and Settlers, is about Lando’s early years in Kenya and later in a boarding school in Goa. In the second book, it becomes evident that in the first book, Menezes was portraying the typical Goan and setting the stage for launching More Matata.

And who is a “Goan?” Historically, a Goan has always been identified as being a brown-skinned individual, born in Goa, of the Catholic faith, with an English or Latin first name, and a Portuguese last name. The Hindus born in Goa were referred to as ‘Hindu-Goans.”

As to what a Goan is all about, this has been the source of endless opinions offered by various discussion groups, pointing out a double standard stemming from the perceived conflict between Goans’ devotion to the Catholic religion and their alleged practice of subtle caste distinction. When seen through the eyes of Lando, a boy with a non-judgmental but inquiring mind, it becomes very clear what the real Goan is all about.

In More Matata, Lando is a keen observer of social and political events that are taking place around him in colonial Kenya, and he questions them in his mind with candor and a delightful sense of youthful humour. As one reads through the book, one can’t help but put oneself in the shoes of Lando and/or his parents and begin to understand why Goans have a mindset that is distinct from other Indian societies.

The book amplifies the various factors that have influenced the make-up of Goans — the underlying ancient Hindu culture, the Portuguese-instilled Christian values, the sense of loyalty acquired through devoted service in the British Colonial government — all of which have stood them in good stead in bygone years. For those who lived in Kenya or any of the neighbouring countries in East Africa during the Mau Mau uprising, More Matata will also make one realize that they lived through a historical colonial era and were witness to a momentous period in the transition of Africa from colonialism to independence.

Menezes is a fine writer, and I had no matata following the smooth, informative and altogether entertaining, narrative.

Ben Antao is part of the Goa Book Club in Toronto.

What I found most attractive about the second book of the Matata trilogy by Braz Menezes is the cover that shows a couple of zebras courting in a Masai Mara game reserve in Kenya. “The shorter one being the female, tries to jump up and kiss the male on the lips, the male raising himself on his hind legs playing hard to get, staying just out of reach,” writes the author.

It’s a beautiful photo that captures not only the theme of the novel subtitled “Love after the Mau Mau,” but also causes more matata (trouble) to the protagonist Lando and his love interest Saboti, a nusu-nusu (mixed race) girl of Masai breeding who had attracted Lando when he was 10 years old in the first book.

In this second offering, there is more autobiography embellished by memory and imagination than fiction. The reader gets a short history lesson on the Mau Mau rebellion against the British colonial rule that began in secret among the Kikuyu tribes in 1950 and ended in a state of emergency when the Europeans were terrorized and killed by the Mau Mau, leading to the arrest and imprisonment of their leader Jomo Kenyatta in October 1952.

During this uprising, Pio Gama Pinto, a Goan in his 20s who worked for the East African Indian National Congress, lended his support for the Kikuyus and their demand for land reforms. Called a communist by the Goans, Pio is also arrested and imprisoned.

Lando and his friend Savio had first heard Pio address a meeting in Nairobi’s Goan Gymkhana. Pio says, “Inequalities will not exist in Goa if it becomes part of India, but we must first rid ourselves of Portuguese oppression. Everyone — even from the lowest caste — will now be able to hold his head high up in India. Nobody should have to go to bed hungry every night. Nobody should live in slums, nor have to step over shit in open drains outside their front door.”

For Lando, the Goan held as a role model is the lawyer J.M Nazareth, advocate of the Supreme Court of Kenya by 1933, president of the East African Indian National Congress from 1950-52, judge of the Supreme Court in 1953, president of the Law Society of Kenya I 1954, and president of the Gandhi Society of Kenya.

But the book comes to life after Lando graduates in architecture and pursues Saboti who lives in Eldoret. Saboti’s story is an eye opener for Lando who “grew up happily in a segregated society, protected by parents and community, where we accepted the political and social hierarchy as if God ordained it.”

As he learns more of the colonial rule and its abuse of the native Kenyans, Lando’s heart reaches out and he falls in love with Saboti. As he contemplates on the scene of the flirting zebras, he comes to realize the depth of damage caused by the great injustices of religion and colonial practices. Like Saul on the road to Damascus, Lando is “blinded” by the revelation of the human condition. His desire to marry Saboti is frowned upon by his parents.

Still, Lando would not be deterred. After Kenya’s independence in 1963, Saboti moves to London. Now Lando’s sister also lives in London. The lovelorn Lando makes one final try and seeks out his darling with a marriage proposal. They meet at a bistro. He notices a ring on her finger. She’s pregnant. With tears in her eyes, she returns the photo of the dancing zebras that Lando had given her more than five years ago, with an inscription “Saboti – Thinking of you, Masai Mara, 1962.—Lando.”

This story of Lando and his friendship with Saboti moved me deeply. It will move you too. So I recommend this book for your reading pleasure.

James Russell is a Canadian author.

As if timed to coincide with a landmark British High Court ruling in October 2012, that allows three elderly Kenyans, arrested and tortured under British colonial rule, during the Mau Mau insurgency in Kenya, to claim damages from the government, a new book by a downtown resident and Canadian author Braz Menezes provides an excellent glimpse into that period of history.

More Matata: Love After the Mau Mau is an intricately layered story rich with historical significance and youthful innocence. (“Matata” is Kiswahili for “trouble”.) Throughout More Matata, Menezes impresses the reader with his knowledge of Colonial Kenya, and his ability to paint, with well-chosen words, the colourful and compelling backdrop of 1951 Nairobi. But the tapestry never overwhelms the foreground, as Menezes manages to maintain the story’s focus on the frustrations and turmoil of a young boy caught up in the eye of social change. Festering all around him — in the countryside and slums of Nairobi, and indeed, the social fabric of colonial — is the more sinister and deadly matata. The trouble of revolution.

The Mau Mau began its campaign to rid Kenya of colonial rule and like many other native-born Asians, Lando is both bewildered and terrified of the Mau Mau, a militant Black African nationalist movement, which, some say, finally convinced the British government to pack its bags and leave. Much of Lando’s uneasiness is rooted in the racial and caste system. The system has assigned Lando, his family, and all other Asians to a centuries-old privileged status a rung below Europeans but above black Africans. Lando’s vaulted social status and economic future is rendered tenuous by the powerful winds of revolution and the stench of repression.

Against this backdrop of murder, mass detention, and mayhem, Menezes weaves an endearing story of adolescence, friendship, love lost, then found, then lost again. When Lando falls hopelessly in love with a woman of mixed race, his father forbids the marriage. “How hypocritical we Goans are — Catholics on Sundays, and practicing a Hindu caste system the rest of the week,” his mother shouts at his father.

Throughout this story, it is Lando’s voice and presence that drives More Matata. And throughout the book’s 300-plus pages, Lando succeeds in not only holding our interest with his coming-of-age story, but manages to get our heart racing on more than a few occasions.

Having read the first and second books in Menezes’s trilogy, I am looking forward to the third instalment by this talented storyteller.

Exquisite reading. Simply loved the second book of the Matata trilogy by Braz Menezes. From the impressively splendid cover photo showing the love-live-sing dance of the two beautiful zebras, to the last chapter.

The bittersweet love story of Lando moved me deeply. And I truly enjoyed another short history lesson about the cruel Mau Mau Rebellion this time, thank you Braz!

Fascinating. I definitely recommend this book for everyone’s reading pleasure.

Another excellent book.

Loved this book. Easy reading. Many lessons learned about Goa, Kenya, British Colonialism, and growing up in a multicultural environment.

Great book on the history of Goan immigration to Kenya and life there and in Goa. Humorously told with a so much history. The author takes you through his story and it is hard to put the book down as each page is full of interesting happenings!

Few authors have the ability to cover major socio-political from personalised perspective, that produces a novel which blurs fact and fiction so skillfully that even the scholar of that history becomes totally engrossed in the novel. Youth and early adulthood in colonial Kenya are staged against a background of African aspirations and European Settler fears, which have parallels in other settler-run colonies. Menezes weaves the varied and polarised sentiments in the lead to, and arrival of independence in Kenya. The difficult position of various racial and ethnic minorities is brought to the forefront, through lived experiences that have a direct relevance to all peoples touched by the spell of Kenya. As a sequel to Beyond The Cape, through the character of Lando this is a wonderful humanising of a crucial part of the history of Kenya that has strong relevance to the country in the early twenty-first century.

Excellent reading, enjoyed thoroughly and it took me down the memory lane as I lived in the area from where this book evolved..very good facts of all the events.

Excellent book about Kenyan history, as well as, a very interesting story. Well done, Braz Menezes for writing a wonderful book. This book has the perfect balance of historical information and entertainment. I am from Kenya and I can assure very few books are as good as this. Worth every penny!

Thousands of Goans made East Africa their adopted home. The lives of Goans in Kenya, Mombasa and Uganda, to mention but three, are intertwined with the cultural and political scenarios of their time in their respective countries. Many Goans rose to eminent positions in government as well as in politics. Braz Menezes, a Canadian-Goan, has attempted to bring to focus through his protagonist life as a child in Kenya and then as an adult working and falling in love in the time of the Mau Mau guerilla revolution that rocked British Africa and led to the Independence of Kenya, resulting in an exodus of Goans to England, Canada, and Australia.

In Just Matata and More Matata, Menezes has weaved an interesting tale of Goan diasporic life. The books are said to be historical fiction and centre on the life of Lando as he grows up, goes to school in Kenya and moves into the working force of a young nation. It also encompasses Lando’s brief sojourn to the land of his parents’ birth Goa, and to St. Joseph’s in Arpora, one of two schools in Goa, which attracted children of the African-Goan diaspora.

Just Matata: Sin, Saints and Settlers is like any other coming-of-age story. Two of the noteworthy recreational spots for Goans, the Goan Institute and Goan Gymkhana, form a backdrop to the way Goans lived and enjoyed themselves. Caste, as much as in Goa, played its part in keeping the Goan community divided. The old Portuguese-Goan lifestyle was transported to Africa, lock, stock, and barrel. Menezes provides glimpses into the way Goans lived in the multi-racial society, which included Indians, though Goans looked upon themselves as different from the Indian stock, and Britishers. A substantial part of the history of Dr. Ribeiro Goan School is laid out. The school formed the breeding ground for many Kenya-Goans who later took on wings in the working world and many who built their lives in foreign lands.

The first book sort of lays the groundwork for the reader for the second book, More Matata: Love after the Mau Mau. Here, Lando describes his homecoming and return to Dr. Ribeiro Goan School, and the school politics that forced many students to the Asian school. Here, we meet Dr. A.C.L. de Souza, the board chair of the Goan school. He’s a Goan leader who was one of the founders of the Goan Gymkhana, which came into being in 1930 as a breakaway group from the Goan Institute. We also meet the founder of the Goan school, Dr. Rosendo Ribeiro, whose picture of himself riding a zebra has remained enshrined in the minds of Kenyan-Goans. The other notable Goans such as J.M. Nazareth and Dr. Fritz de Souza are also given reverence for their outstanding roles.

Then there is the introduction of Pio Gama Pinto and the mention of the Mau Mau, a bloody revolution that shook the roots of British Africa and eventually led to Kenya’s Independence. Setting his eyes on Pio da Gama for the first time at the Goan Gymkhana, Lando is astonished to see a “real Communist” and that too from the Goan community. Lando finds Pio inspiring and is in agreement with Pio’s political mantra. Pio, who is the son of Anton Rosario Pinto of Socorro, and as much loved and hated by Goans. He’s Kenya’s first martyr of independence.

The thundering voice of Pio is captured as he espouses the cause of Kenyan nationalism and calls upon the Goans to support their “African brothers” and eliminate their suffering. It’s beyond doubt that the Mau Mau caused a rift in the Goan diaspora, some worried about their future if Kenya got its freedome and some were fiercely loyal to the British colonists, as many had their family members working for the civil service. Menezes provides insights into the Mau Mau and how it spread panic into the Indian diaspora. Goans were caught in the middle of the two warring sides. The Mau Mau killings are graphic in details, and the trial of Jomo Kenyatta, the leader of the Mau Mau, who later became the nation’s first president is given a good amount of space.

In the mix of things is also thrown in India’s fight for Independence and the division of the united India into India and Pakistan. Nehru gets a mention for his role in the freedom of Goa. The issue of Goans as “different” from the rest of India is fought between Goans. Menezes takes pain to paint the political climate of the day in Kenya and how it affected the Goan community. He tackles issues such as racism, caste, and nationalism, subtly in the context of Kenya and of Goa.

In the midst of the Mau Mau trouble in the country, Menezes spins a story of love between Lando and a half-caste girl (born of a white father and Masai woman), Saboti, who misinformed Lando that she’s a Seychelloise, when he first met her when the two were small children during his family’s safari to Kericho in 1949. He was instantly attracted to her.

Thereafter, a chance meeting brought them together and they began a fairytale story of friendship and love that took a meandering course of distant places and different circumstances. It highlighted the issue of internationality and inter-caste relationships and marriages in the Goan society. The issue of mesticos or half-castes also gets pinpointed.

Lando’s busy lifestyle delays him in writing to Saboti, who thinks family pressure keeps Lando from maintaining the relationship. She marries a Britisher, and has children.

In the epilogue, Menezes writes that Lando accidentally met Saboti in London after 44 years, at the Tate Modern Museum. They have dinner like in past times, and she adds to her story of her years in London, her widowhood and her children. At the Heathrow Airport, waiting to leave for Toronto, he promises her that he would call her.

The Lando-Saboti story runs like a heart wrenching thread throughout the book. Maybe, Menezes has more of this poignant story in the third book, which should round up the trilogy of a Goan lad, the Kenya he loved, the Goa he experienced, and the woman he lost.

As an American-born girl (late 1952) who grew up in Karen-Langata, who was schooled at Nairobi Primary and Limuru Girls’ Schools, and who worked at AMREF at Wilson Airport between 1961-1981, I was absolutely riveted by the first two books of the Matata trilogy, which I read on Kindle in rapid fire succession, they were so good! Excellent is actually the better accolade! Braz Menezes really captures and conveys the whole Kenyan experience, such that the reader can practically smell it.

I both laughed and cried at his depictions of the various situations in which he found himself, a true rarity when reading memoirs and one which can’t be over-appreciated. I want to thank Menezes so much for sharing his life so intimately and vividly! His books are just gems!

For June, July and August of 1960, when my parents were deciding on which of the three East African countries they wanted to settle down in order to start their photographic safari company for American tourists, our family of five resided at the Sinbad Hotel in Malindi. There, my younger brother and I (six and seven years old) were befriended by the son of the hotel’s Goan head chef, Peter Menezes. Peter was an apprentice chef at the time, and used to give us handfuls of hot roasted nuts out the back door of the Sinbad kitchen. He would also come swim out front with us in his spare time, allowing us to jump off his broad shoulders into the on-coming waves. Menezes’ book reminded me so often of Peter, such a gentlemanly gentleman. He was probably all of 20 years old at the time, but to us, he was our hero and he set a lifelong precedent in our minds that Goans were special people!

We encountered him again over our return to the Sinbad a year or two later, but then my parents (who had divorced by then) each bought a house in Malindi whereupon we didn’t frequent the Sinbad on our school holidays. We thus lost touch with Peter and his father, but I have often wondered over teh years what ever became of them. I have a feeling they might have emigrated to another country, as so many Goans did around Independence — much to Kenya’s detriment, if you ask me. I just hope that whatever their fate, it wasn’t a cruel one.

Like Menezes, my stepfather, who was born in Kenya (1933) and raised in the Aberdares, worked pre-Independence with Tom Mboya to try to help Kenya gain Independence. I’ll never forget celebrating in the streets of Malindi on my eleventh birthday on December 12, 1963!

It was an amazing country in which to have had the good fortune of growing up because of its multiculturalism and the rich experiences not readily found elsewhere on the planet. I wouldn’t change my background for anything!

I’ve GOT to find out what happens next! Thanks Menezes for two terrific reads! I’ve highly recommended the first two books to all my Kenyan friends and family.

These books are absorbing reading. They combine the social history of a family and community with thorough historical research that informs the reader of Kenya’s political evolution. If you haven’t done so already, be sure to read Just Matata: Sins, Saints and Settlers and its sequel, More Matata: Love After the Mau Mau by Braz Menezes, a former renowned Kenyan architect-turned-author.

Partly autobiographical, the books chronicle the culturally rich and colourful coming-of-age story of a young and precocious boy and his traditional Catholic Goan family in pre-independent Kenya. Told from the perspective of Lando, he describes how his father ends up in Kenya in 1928, putting down roots originally in Mombasa and then in Nairobi, before returning to Goa briefly to gain a wife in 1935.

Lando, born as WWII breaks out in Europe, grows up across the road from the Parklands Sports Club (Europeans only) and within walking distance to the then Coryndon Museum. He experiences a traditionally Goan upbringing, superimposed over a typically adventuresome Kenyan boyhood, before he sets off at the age of eleven to a Jesuit-run boarding school in faraway Goa. But, he manages to escape. This is followed by an even more complicated, but equally rich and valuable teen years during the Mau Mau, as he forges into virgin terrain at an Asians-only high school in Kenya, and later into the first multi-racial class at what was the inqugural Nairobi University. His apprenticing internships at various architectural firms are thought-provoking, as are his anxieties about inter-racial relationships and marriage.

You’ll laugh, you’ll cry, and even learn through the culturally interesting eyes of the young Goan-Kenyan. You’ll also be taken down a wonderful memory lane full of anecdotes about growing up in Kenya including masala-spiced mangos, the museum and the Leakey family, a first safari, a memorable family picnic in the Rift Valley, shopping in the Indian Bazaar, a family visit to Old Town Mombasa, a return voyage by steamship to Goa, and a glimpse of life in boarding school. Lando also has a bossy older sister, a loyal dog named Simba, and a compelling schoolboy crush.

The two books really are must-reads for anyone who ever grew up or lived in Kenya (and curious tourists) wanting to understand the historical social fabric, then or now. I am enthusiastically sharing my reactions, as I believe other readers will absolutely enjoy reading Just Matata and More Matata. Buy them today and then, like me, yearn to find out what happens next in the still-untitled, soon-to-be-released third book. Happy reading!

I have just finished this book after reading the first in the series, Just Matata: Sin, Saints and Settlers. I absolutely loved these books, which are well-written and fast-moving. Having been born and raised in Kenya myself, Braz Menezes’ books were especially interesting to me for their insight into what life was like in this most beautiful and wonderful African country.

However, not everything on the surface was as it seemed, for it hid a darker side during Colonial times, and Menezes has really brought this to light — the struggle for independence, the difficulties faced by non-white Kenyans as the colour bar was enforced, and the most painful being the horrors of the Mau Mau. Being in the thick of these times as a schoolboy and young university student to his first love and exciting career working on Kenya’s first wildlife tourist lodges, Menezes’ hero Lando is an insight into the life of a young Goan man during that period.

Hakuna Matata is a foot-tapping ditty that became popular the world over after the release of The Lion King. It means “no problem” or “no trouble” in Swahili. However, Kenyan architect-turned-author Braz Menezes uses matata, which means “trouble”, in the titles of his two books: Just Matata: Sin, Saints and Settlers and More Matata: Love after the Mau Mau. These are part of a trilogy (the third book is currently being written).

This is faction, or fiction based on facts. These two books are semi-autobiographies of the author who lived in Kenya during the colonial era, qualified as an architect/urban planner and worked as a respected professional until 1976 when he migrated to Canada. Then he studied creative writing and morphed into an author. Menezes recreates the joys, heartbreaks, frustrations, and the good life in the unjust and violent colonial Kenya in the ’50s and ’60s.

The second book is set during and after the bloody and brutal Mau Mau Rebellion, so called by the Colonials, and renamed Freedom Struggle by the Kenyans after tehy wrested the country’s independence. Mau Mau guerrilla fighters were dubbed “terrorists” by the colonials and renamed “freedom fighters” by the Kenyans after independence.

Menezes describes the daily life in two colonies: Kenya ruled by the British, and Goa ruled by the Portuguese. Mau Mau, the horrendous episode in Kenya’s history from 1951 to 1956, took a massive toll of lives. Between 12,000 and 20,000 Africans were killed by British forces that included 10,000 soldiers, 21,000 policement, and 21,000 Home Guards. The forest fighters killed 32 white settlers in all and about 200 British soldiers and local policemen.

The causes of this uprising was rooted in the Africans resenting their land taken over by the white settlers, thus making them landless labourers, and the racial discrimination practiced by the rulers. Africans were not allowed to grow cash crops. Plus, the unjust colour bar in education, health, law, housing, jobs, and all sectors was strongly grudged. When the Africans had enough, the violence was brutal. When the Mau Mau attacked an isolated farm owned by a white settler, they killed him and his family in a horrendous manner. In retaliation, the British Air Force bombed the forests hiding the Mau Mau, while the ground forces were ruthless in killing Africans en masse. Tens of thousands of Africans were imprisoned and tortured to confess in so-called detention camps up to 1960.

Kenyan Indians were also caught in the cross-fire. Officially, the Indian shopkeepers in the rural areas had to demonstrate their loyalty to the British rulers, but also support the forest fighters from the back door, lest they be butchered. Despite this strategy, 26 Kenyan Indians were killed. African historians have dubbed this struggle as the greatest war for freedom in Africa. Some Mau Mau detainees have succeeded in getting some compensation for their suffering from the British government.

More Matata: Love after the Mau Mau describes this sad and brutal period of Kenyan history and the coming-of-age of the protagonist, Lando. He was 10 years old at the start of this narration. The novel traces his coming-of-age as the Portuguese leave India in 1961 and Britain departs from Kenya in 1963, almost a decade after the horrors of the Mau Mau.

In this turmoil, the Goans were loyal to the British and worked as bartenders, tailors, clerks, chefs, bakers, mechanics, bookkeepers, and musicians who kept a low profile, but enjoyed the good life in their community clubs and societies. They spoke good English, wore western clothes, danced the waltzes and fox-trot, listened to rock ‘n’ roll, and enjoyed their drinks. So in their lifestyle and as Christians, they were close to the British. As the Mau Mau came to towns, Lando’s life turns dangerous and more matata (trouble) erupts when he starts romancing across racial boundaries.

Thoughtfully, Menezes has included an introduction that sets the scene, two maps where the action takes place: Kenya and East Africa, and India, with a glossary of Swahili words and other abbreviations. In this book, the docile Kenyan Goans are not just marginal to the story; they are at the center of the action.

I bought Braz Menezes’ first book, Just Matata, on a whim, having been brought up in pre- and post-colonial Kenya. I was captivated by Braz’s style of writing and his vivid portrayal of places and incidents seen through the eyes of a young Asian boy, born and living in Kenya. I left wanting to know more of what would happen to the subject, as he faced tumultuous times ahead. Therefore, buying his second book became a must.

I was not to be disappointed. Continuing in the same easy reading style, the book opened my eyes to a number of social injustices that I, as a fairly privileged expatriate Kenya youth, was basically unaware of, and carries the reader through a journey of life and history in the making, as Kenya struggles to establish its direction and future identity.

As with the first book, it is a modest and innocent account of the author’s experiences in a country where despite being born there, speaking the language, and holding the passport, movement, expression, and association were severely limited, not to mention the right to education, medical services, employment and just about every other basic human right, that was denied on grounds of race, or more bluntly, colour.

Through clever use of dialogue, the author successfully brings what is basically the autobiography of a boy enduring changing times in MacMillan’s Winds of Change to the present, making it more interesting and perhaps vivid. There are frequent humorous observations and insights on interesting aspects of contemporary life in Kenya and the fragile existence of the very respected Goan community that played such an integral role in the development and maintenance of pre-Independence Kenya.

More Matata also provides a very balanced insight into the Mau Mau rebellion and its causes and effects on the native population in particular. It also discusses the run up to Independence and the sentiments experienced as the Union Jack was lowered on what was a cornerstone of the diminishing British Empire. Whilst it is perhaps very much in vogue to take a swipe at the apparently brutal manner in which rebellions and uprisings were handled by Colonial governments, Braz avoids this by making his observations and leaving it up to the reader to make his own conclusions. A point in fact is the disappearance of his African houseboy and family after being taken away by the police in the middle of the night and his family’s desperate, but subsequently futile attempts to locate them or understand what happened to them.

This is an excellent read and, again, I am left wanting to know what happens to Lando, through another period of uncertainty, that me and my family, like so many others was yet to experience.

I greatly look forward to reading the final book in the Matata trilogy.

Excellent! Like Braz Menezes’ first book in the series, More Matata is a compelling read that grabs your imagination. It is brilliantly written and the story flows easily capturing the quintessential spirit of colonial East Africa, whilst providing a wealth of information and historical facts that too easily can be lost and forgotten.

Having learnt so much about Goa in the previous book, I now learnt a whole lot more about the Mau Mau and how it affected so many in Nairobi. I was heartbroken when Mwangi, his wife, son Stephen and the baby were rounded up and they never saw them again. I almost feel we missed all this up in the Highlands.

I loved the tales of growing up as a teenager and adjusting to a non-Catholic school and then on to college. I could feel the romance between Saboti and Lando, she was so ideal for him, except the trouble he would get from his parents. Loved hearing about the different trips to lodges and treetops, to build and expand.

Now I look forward to the third book. I feel I have had a history lesson, what an adventure it has been. Lots of sleepless nights and good reading!

Braz Menezes, already a recognized writer, emerges here as an adept and highly skilled long-form storyteller as well.

The story is that of Lando, from his early days as a Catholic schoolboy in Kenya until that country’s independence in 1963. (His origins and family history are covered in more depth in the first book of the trilogy, Just Matata: Sin, Saints, and Settlers.) There is little doubt that it is Menezes’ own narrative, based on his experiences and impressions augmented by family legends and careful research. Central to the book is the profound and sensitive love story that is woven through Lando’s life, in unobtrusive episodes, from age 10 to his middle years. But this is much more than a tale of one life and one love.

In his after-note, the author says his intention is to enrich the existing literature on Indians in East Africa (by M.G. Vassanji, et al.), by bringing to light the extensive but little-known influence of the relatively few Goans there, migrants from Portuguese India. This he does, with great success — but without ever “teaching” history. His true-to-life characters live it in their day-to-day activities. The circumstances of life in Goa and Kenya, and the realities of the times — Jomo Kenyatta and the Mau Mau uprising, the struggles in Africa between the disparate colonizers and native peoples and immigrant groups, developments in Europe — unfold naturally as they touch the Goan community and the lives of the characters. There is no clumsy narrator overview: the contemporary international and regional events enter the story organically, via the BBC World Service on short-wave, national and local newspapers, and of course rumours and gossip.

Menezes has an acute ear for the rhythms of conversation. He uses dialogue extensively to advance the story, to give the scenes much of their local flavour, and to enhance the characters’ authenticity. He introduces considerable suspense, and resolves it with a deft hand — in the love story, in Lando’s maturing, in the family’s internal dramas, and in the political environment.

It is a rather long book: sweeping in scope, full of details and images and background. But it is not long in the reading — it moves along smoothly and is endlessly fascinating. The reader soaks up the ambience with eagerness, and truly cares about the characters and the events and the outcomes.

Menezes tells us that matata is a Swahil word for trouble. But if you’ve hesitated to pick up this book because you guess from the title that it’s just for an “ethnic” readership — hesitate no longer. It is for every reader who loves a powerful and well-told story about real people in the real world. Including this unrepentant Muzungu (white person).

Though Kenyan born and raised until I was around nine, I’m ever so grateful to this masterful word/image craftsman Braz Menezes for filling in so many gaps which I was unaware of as a child growing up.

This book building on the first in the Matata trilogy is if anything even more searingly poignant, bittersweet, joyous and inspiring to the soul and mind.

It narrates no sugar coated whispers nor illusions about life in the colonial East African-Goan, etc. experiences of cultures, hearts and lives divided cruelly often by mere race economics and politics then and even now often obtaining, but never defeated by sheer raw humanity, spirit and kinship.

These books should really be on suggested reading lists in schools both in Kenya, Goa and other multi-heritage lands of the diasporae, so the respective contributions to that era are even more appreciated and not forgotten.

As it is, there are precious few Goan Kenyan authors who have captured those images so exquisitely.

One can hardly wait and at the same time dreads the arrival of the final book of this trilogy…with a cry of say it ain’t so “protagonist” Lando.

Such a well told story. I can just imagine being there and experiencing Kenya and Goa with the author. Fills in some blanks in my own family history as my father was from the same generation and would have done many of the same things! Excellent easy reading!

Would recommend to anyone who wants to have an insight to Kenyan/Goan history of the ’40s through to the ’50s.

In Braz Menezes’ first book in the Matata trilogy, Just Matata, I grew to love Lando and his attitude towards life, and I was looking forward to reading the second book, More Matata. It did not disappoint!

Lando, the oldest son in a Goan family returns to Nairobi, Kenya, from boarding school in Goa at the age of twelve, just as the rumbling of trouble, the Mau Mau Emergency is brewing. He draws you into his life, and his journey to maturity is brilliantly portrayed by Braz Menezes. The subject of puberty and Lando’s first girlfriends is written with sensitivity.

For me, being born the same year as Lando means that I can relate to many of the events mentioned, but I have learnt so much. I think many of us, mzungu (whites), had friends in the Goan and Indian community, but never stopped to think that we were privileged. Lando, as a newly qualified architect, comes to understand the problems and looks forward to Independence from Colonialism. He realizes that he has been living in a “segregated society, protected by parents and community” in which they accepted “the policies and sacred hierarchy as if God ordained it.”

With my brother fighting with the Kenya Regiment against the Mau Mau, and interpreting in Court when Kikuyus were being tried, I heard one side of the story. This book deals with all aspects of the Emergency and we learn much of the history of that period. This is of interest, not only to people like me, but also to those who have never been to Kenya, but wish to read a fair and balanced account of that disturbing time.

This book is also a love story; Lando’s love of Kenya and also his love for Saboti. I challenge you to read about Saboti and not have tears in your eyes—impossible!

I can thoroughly recommend this book. I still love Lando and his views on life as a young man and I look forward to the publication of book number three.

As I turned over the final pages of More Matata: Love after the Mau Mau, I felt a nostalgic yearning for the homeland I’d left behind almost 40 years ago. Through 307 pages of More Matata, I was transported to a time and place that I held, and still do hold, dear.

Reading about the Coryndon Memorial Museum brought back memories of truancy at skipping class just to “hang out”. Where else to be undiscovered, but at the museum with its myriad of hiding places? Menezes breathed life into the now forgotten streets of my beloved Nairobi. He awakened dormant memories of a splendid past life, and a realization that our Goan forebears, and later their offspring, can indeed boast of an intrinsically rich and vibrant participation in the mosaic of communities that contributed towards the building of British East Africa, which later became Kenya.

But, more than merely traipsing down memory lane, Menezes jogged in me awareness into the disgrace and pain of the odious practice of segregation that was prevalent during the time of British East Africa. On a personal level, I was not old enough to comprehend, nor be affected by, the full impact and implications of the “colour bar” that was imposed by our Colonial rulers. The shame that was “For Whites Only” became a reality my parents protected me from — the degradation of not being allowed through the front door of buildings, or not being served in certain “White Only” restaurants. My parents didn’t discuss the atrocities inflicted upon persons of colour in front of me, and thus I never really understood how painful and hateful such practices were.

Being raised Goan, we were bogged down with our own community biases of caste and profession. One was considered ineligible for entry into clubs and socials if one was born into the house of a tailor, a cook, a baker, or such. But, none in our community were considered worse than those born nusu-nusu or half-caste. Sadly, these were dirty words among most people; even in the homes of those looked down upon by Goans of imagined higher birth or trade.

Turning the pages of More Matata, Menezes has brought to light the heartbreak this evil has wrought on the lives of so many innocent people. In his very poignant story, I felt a deep sadness and regret for Saboti’s missed opportunity of true love. Yes, I am an incurable romantic.

The Mau Mau era was also a phenomenon I was shielded from by protective parents. My generation left it to our parents and their generation to worry about the harsh struggle towards an independent Kenya, and the breaking of the yoke of suppression by the British rulers of the Empire. But, within the pages of More Matata, the icons of the fight for freedom like the once dreaded Jomo Kenyatta, Dedan Kimathi, Pio Gama Pinto came to life again. These were household names that everyone knew about. Only, one just whispered these names in the privacy of homes, or perhaps the more daring would talk about them in their clubs. It was vaguely familiar, and exciting to revisit that forgotten era again.

Thank you, Menezes, for having taken me on this journey through a country that I once loved. The memories you evoked are precious. I wholeheartedly recommend that everyone read this book. If you haven’t read Just Matata, do that first. Whether you are a Goan born in Kenya, or just a Goan; whether the perpetrators of segregation are your forebears or whether you are the victim of this evil, read the book. A thoroughly enjoyable trilogy.

Just wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed the second book. I really loved the way it was written – it gave me a lot of insight into the Kenya you & Niven were brought up in and helped me conjure up pictures of your parents who I would have loved to have met. I hope the third book is on the way. Even if you don’t sell many copies you can be proud of having written something so brilliant, entertaining & capturing all the historical aspects of Kenya before Independence.

I have just finished More Matata and loved it. Impressive! Fast Moving! Great descriptions!

Best history lesson — ever — about colonial Kenya!

I read it in two sittings and enjoyed all the personal stories intertwined with such vivid depictions of what was happening in Kenya after WW2. I felt the story line moved even faster and was more riveting than Just Matata. It really was a thrill to learn about how Lando became an architect and to learn about his early projects. The emotional background story of Saboti was powerful but even more so when Lando accidentally met her on the steps of the Tate Modern and then their 15-minute telephone calls during the 2008 American election.

An excellent book about a young Goan boy growing up in Kenya. It builds on the first of the Matata trilogy and gives an insight into colonial Kenya during the time of the Mau Mau. Orland, the protagonist, attended the first multiracial college in Kenya. He meets up with his childhood love who is mix-raced being the offspring of a white farmer and his Maasai mistress.

The story is told with tremendous empathy and understanding but still reveals the cruel divisions caused by race and economy. Braz Menezes helped me to fill in lots of gaps in my own Kenyan upbringing. I had never realized that the Independence of Catholic Goa could cause such a dilemma for a lot of the older generation of Goans living abroad.

Definitely a “must” even if you are not a Kenyan, Goan or otherwise.

I just finished the second volume in Braz Menezes’ biography and was captivated by the parallel tracks — the sweeping drama of a nation coming of age, and the unique history of a young Goan man growing up in Kenya. The political and ethnic strife sharpened his determination to do well in architecture, a profession that fell into his lap while civil war swirled around him. A colourful cast of family members, locals and an irresistible girl from the wrong part of town make this an engaging read. Very enjoyable!

This book is a welcome addition to the first book, Just Matata. Braz Menezes takes us through a vivid journey during a time when Kenya was still a very segregated society. Lando, the subject of this novel returns to Kenya from boarding school in India and settles back in his Goan community.

The Goans are a specific race from the Indian subcontinent that stand apart from other Indians by their customs and heritage. Goans are Catholics and most speak Portuguese since they come from a part of India that was a former Portuguese colony. The Goans even have their own private school in Nairobi. Lando is unique in transferring to an Indian school where a majority of the teachers are British.

This is a time of great turmoil in Kenya and Lando uses his keen sense of observation to record daily events around him. The local Africans are beginning to call for independence from Britain. The secret sect called the Mau Mau struck fear into everyone with their sudden attacks carried out with great brutality. It is in this background of turmoil that Lando describes everyday events that bring into sharp focus the customs of the Goans and their strict moral upbringing. To add to Lando’s inner turmoil, he falls in love with a girl of mixed race — a definite taboo in his culture. This intertwining of forbidden love, politics, race, culture and customs is skillfully handled in this novel. It will grab your attention from the first page and will keep you turning pages in anticipation of each new development that occurs in rapid succession.

As one who lived in Kenya during this period, I found this novel to be a nostalgic reminder of a unique period in the history of Kenya, when a long segregated society saw racial barriers slowly disintegrate with impending independence. Menezes masterfully handles this period of turmoil in a manner that brings to life all that was so unique and wonderful about this part of Africa. I highly recommend this book to all those who are looking for a good read. I look forward with great anticipation to the third book in this trilogy.

I enjoyed JUST MATATA over a very long read! It could be that I was familiar with the situations, and had to follow carefully the places and the characters, so as not to lose the plot! Lando’s story as a young boy shunted to Goa – to a boarding school, like many others had to leave home either for a good education, keep out of trouble or for safety during very turbulent times in Kenya.

MORE MATATA has been written with experiences felt from the heart. The love for Saboti from a young age never really went away and it seems to have followed Lando through his whole life whilst in Kenya and later. I was not able to put the book down, as each chapter brought a new experience and a feeling of excitement and anticipation as the story unfolded!

As a young Kenyan myself, I never really understood racial discrimination or colour bar. Our schools, clubs, social gatherings, sports activities, etc. as I know them now were exclusively for the Goans, Mzungus (Europeans) Africans, Indians, which within themselves were classified as Sikhs, Muslims, Hindus, Parsis, and the list goes on!

More Matata is a ‘Must Read’ for everyone who lived in Kenya, and indeed anyone interested in the history of Kenya. Waiting anxiously for the last in the trilogy!

A great book. Mr. Menezes writes about the life and times of a young man growing up and living in Kenya under British Colonial rule, the racial tensions it brought about. But it is also about a love and romance that follows, makes compelling reading — I could not put this book down until the very last page.

Great sequel to the first book. I could not put it down! It took me back to my childhood — wonderful book!

This second book of the Matata trilogy by Braz Menezes is a beautiful and bittersweet love story, not just between two young people, Lando and Saboti, but also between Lando and Kenya, the country of his birth.

Matata means trouble. The story begins when Lando returns to Kenya after a period of schooling in the Portuguese colony of Goa where his parents had lived before their immigration to Kenya. Through Lando’s eyes, we experience the seething racial tensions and terror during a time of profound political and social change.

As a Catholic Goan, Lando is caught in the colonial system that classifies people based on colour and discriminates against non-whites. As an Asian, he experiences the barriers that restrict educational opportunities and social interaction. As a teenager, he soon becomes aware of the terror and violence growing around him as the Mau Mau seeks to overthrow the Colonial government. As the eldest son of a peace-loving family with traditional values, Lando faces personal challenges as he grows towards his own independence.

The author brings the history of Kenya and the beauty of the land alive. His portrayal of the excitement surrounding the visit of Princess Elizabeth who became a Queen before leaving Kenya captures the awe and loyalty felt by many toward the royal family. His descriptions of the growth of the Mau Mau and the reactions of the local governments to the organization bring to life both the terror spreading across the land and the increasing realization that the colonial government would fall.

The history of Kenya unfolds while Lando is finding his calling into architecture and early professional successes. Although he enjoys the company of girls in his Goan community, he never forgets Saboti, a young girl of mixed African and English races, whom he met before he left for Goa. Their surprising meeting and renewed relationship is the highlight of the book, but it does not escape serious matata.

With his prologue and epilogue, Menezes puts the events of the sweeping changes in Kenya into a current perspective and shares his personal feelings of hope and love. This is a powerful and moving book.

There are already four excellent and detailed reviews of this fine book. I can only add that anyone interested in Kenya, East African history, race relations, coming-of-age, or just a good story would enjoy this book.

Although I lived in Kenya when More Matata events had already happened, their impact was still visible and palpable. But you do not have to have lived in East Africa to find this story engaging, interesting, and relevant to today. As one reviewer says, “More Matata can stand on its own.

I agree, but it will be even more enlightening and fascinating if you read Just Matata first. In that book, also available on Amazon, the background history of Goa and earlier Kenya provides a wonderful example to understand how this world we now live in has evolved. It is also a fun read!

More Matata is a wonderful coming-of-age story set in a tumultuous time and a beautiful, exotic country. I thoroughly enjoyed this story of young Lando, his friends, and loves as they grow up among racial tensions, prejudice, and violence in Kenya.